Square peg, round hole:

Roguelikes in Termux

The last few months of my time has been on-and-off spent trying to get a number of traditional roguelikes to run on my phone. To me, the idea of being able to possibly play something from a genre of largely-free games that required next-to no battery power and sported a basically limitless amount of replayability on my phone was something of a minor dream! But if you’re anything like me, the idea of trying to control these things with touchscreen controls seemed like it would be painful at best. But the “potential cool” of being able to have portable ADOM outweighed the negatives. So it was at least worth a try!

In this post, I’ll talk a little about my adventures in getting these little RPGs working on an unrooted Android phone!

Now, I’ve seen people play games in emulators on phones before, and the touchscreen semi-transparent control schemes those all used seemed, well…like something I probably couldn’t tolerate for long enough to enjoy any game beyond the initial novelty. Roguelikes also have a habit of using a substantial number of keys on a full keyboard, so layering those over the screen seemed like it would be a major nonstarter. The alternative would be using a portion of the already-tiny screen for all the keys, making the actual game microscopic!

But on the other hand, could you imagine being able to play ADOM on the go? It was definitely still worth trying!

Termux

Termux is a shell and Linux environment for Android, and with it, you can use the command line on your phone like you would on most other Linux distributions. You can install packages, compile code, and even run entire others Linux distributions in proots if you run into limitations of the native environment.

Seriously, it rocks so hard!

It's still wild to me that I slept on Termux for so long

— Arch 💕 (@Archenoth) February 4, 2020

It's a full Linux environment that works on a phone! And while it does have some limitations, the fact that I have a working version of *ffmpeg* on my phone that I installed by running "apt install ffmpeg" is just bonkers

Just the fact that you could apt install things that I had previously thought were impossible to run on Android sold me on using Termux basically instantly. And actually, right in the official game repo, you could install Angband!

$ apt install game-repo

$ apt update

$ apt install angband

Of course, I did that nearly immediately after discovering I could. It’s our first Roguelike, and it took basically zero effort to get running!

But how well did it work?

Controls

As expected, after starting the game it became immediately apparent that controls were going to become an issue. But I also discovered that I didn’t have nearly as much trouble seeing the game in portrait mode as I initially though I would. And even if I did, I could run Angband with lower terminal row and column counts to make things bigger without the game complaining.

This meant that, in theory, I could create a custom keyboard to make things a little less annoying to control, and that would get rid of most of my immediate issues with playing the game. So, paying special attention to the keys I used the most that weren’t easily available on gboard, I wrote a small Termux keyboard layout.

Here is what I eventually came up with:

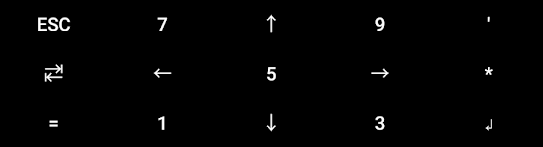

That configuration makes the following appear above my normal gboard keyboard:

You might be wondering, why arrow keys instead of all numbers? Turns out, unlike numbers, arrow keys can be held down to hit them multiple times in these custom key layouts! So if I was going to walk long distances in-game, that auto-repeat functionality seemed like it could be handy. (Also, it’s purty :3)

Turns out, even though I made this key layout for Angband specifically, it ended up working much better than I expected, and I was able to play a lot of other roguelikes with very little modification!

But, I would need to get them running first! So, what were my options here?

Compiling

If Angband was easy enough to get working on Termux, that means that it must be easy enough to compile, right?

Since there are a lot of games based on Angband, and since I already had a working Angband keymap, Angband variants seemed like the logical next step, since a lot of those are very unique and good games themselves.

In fact, this was what lead me to discover Sil!

Enemies are more threatening and have interesting AI, but you also get lots of tactical tools to offset that (Though most choices have tradeoffs)

— Arch 💕 (@Archenoth) February 4, 2020

The setting is a meticulously-researched Tolkien universe, and it's a significantly shorter game than Angband; the game it came from

However, it’s also what lead me to discover my first hurdle with compiling games to play on my phone: The C preprocessor!

Note: I’m using sil-q for the code blocks here because it requires the same process as normal Sil, but it can be fetched with git

$ apt install build-essential ncurses git

$ git clone https://github.com/sil-quirk/sil-q.git

$ cd sil-q

$ nano src/Makefile.std # To turn off things like X11, and enable only gcu

$ make -C src -f Makefile.std install # Errors with ./h-system.h:40:12: fatal error: 'sys/timeb.h' file not found

C Macros

Turns out that a some C files act on the absence of certain flags that are set in specific and predictable environments.

In this case, since Termux on Android wasn’t exactly a “predictable environment”, the lack of any flags that were in #if !defined(THING) chains would sometimes mean that we got some pretty wild pieces of code that would become active, and I would need to hunt for the resulting places that these were included and remove them.

If you just follow the compiler errors, this process is a lot easier than it sounds.

It was especially easy for Sil, I just needed to delete the line that tried to include timeb.h:

$ nano src/h-system.h # I literally just deleted lines 39-41

$ make -C src -f Makefile.std install

The diff was basically

-# if !defined(SGI) && !defined(ULTRIX)

-# include <sys/timeb.h>

-# endif

This worked! I had a sil binary! So, aside from this little bump in the road, the compilation was basically just a standard Linux build. (Which again, I need to stress is absolutely bonkers to me since this is on an unrooted phone)

However, trying to reap the rewards of my compilation, I ran into my second hurdle: seccomp.

seccomp

$ ./sil

Bad system call

On older Android versions, this program would have run just fine, but since Android Oreo, a seccomp filter was introduced into Android that would guarantee that certain system calls would never be called. A lot of these system calls were things regarding user and group ID setting, which is something that Android doesn’t really support with it’s single-user environment. (Here’s a full list of the functions that would be filtered)

The catch with seccomp is that anything that calls a seccomp-filtered function won’t just skip over it–the program that called it will actually be killed by the kernel.

This of course, isn’t a great thing if you are trying to play a game.

How did I discover this? It turned out that strace (An extremely handy Linux tool that shows you all of the system calls a program makes, along with their results) can be installed from the official repos in Termux! So I just ran Sil through that:

$ apt install strace

$ strace ./sil

<output snipped>

rt_tgsigqueueinfo(19612, 19612, SIGSYS, {si_signo=SIGSYS, si_code=SYS_SECCOMP, si_call_addr=0x7e91ce0038, si_syscall=__NR_setregid, si_arch=AUDIT_ARCH_AARCH64}) = 0

rt_sigreturn({mask=[RTMIN]}) = 10202

--- SIGSYS {si_signo=SIGSYS, si_code=SYS_SECCOMP, si_call_addr=0x7e91ce0038, si_syscall=__NR_io_setup, si_arch=0 /* AUDIT_ARCH_??? */} ---

+++ killed by SIGSYS +++

Bad system call

Googling “SYS_SECCOMP” gave me enough hints to eventually discover the above post about the introduction of a seccomp filter in Android, and also the list of functions that were filtered.

Armed with this new knowledge, I saw that __NR_setregid was the function that tripped the filter and killed the game. So I just grepped for it, and deleted those parts of the code (Since again, they were just dead calls on Android’s single-user environment anyway), and recompiled.

$ git grep 'setregid' # It's interesting how the matched .o below has `x86_64` in it's name, since this was very much running on `aarch64`

src/files.c: if (setregid(getegid(), getgid()) != 0)

src/files.c: quit("setregid(): cannot set permissions correctly!");

src/files.c: if (setregid(getegid(), getgid()) != 0)

src/files.c: quit("setregid(): cannot set permissions correctly!");

Binary file src/sil.o.x86_64 matches

$ nano src/files.c # To delete the things that matched above

$ make -C src -f Makefile.std install

$ ./sil

It worked!

I mostly stumbled across it because I've been looking for games I can compile and run on my phone, and I'm happy to say that Sil works excellently on there!

— Arch 💕 (@Archenoth) February 4, 2020

Actually, roguelikes in general seem to have a knack for working much better than they should with a touchscreen in Termux pic.twitter.com/ASGjFlk7qC

And with that hurdle out of the way, it turned out that I could get all kinds of Angband variants working with this knowledge. That included things like FrogComposband, which is a large Angband variant with quests, an overworld, and generally a very significant amount of content.

Cool! With bands out of the way, what else can we get working?

Android-specific code

My next target was Dungeon Crawl: Stone Soup, which had a very interesting problem: It actually has an Android version.

That might seem like a good thing, but that meant there was a lot of Android-specific code that would try to do its thing when I tried to compile it. This turned out to be a headache because Crawl made some assumptions about what an Android version of Crawl should look like. (Perfectly reasonable assumptions, but I’m not coming at this from a perfectly reasonable angle)

The most apparent one was that doing an Android build would try to generate an APK, which my phone was not at all equipped to do. It also tried to build a tiles version by default, which of course wouldn’t fly with the purely-textual terminal I was sporting.

I ended up going through syscalls.cc and inverting all the checks for Android, then tried compiling it as if it were a normal POSIX application so I could sidestep most of the Android-specific code.

This almost worked:

$ git clone https://github.com/crawl/crawl.git

$ cd crawl/crawl-ref/source

$ nano syscalls.cc # I replaced all "#ifdef __ANDROID__" with "#ifndef __ANDROID__"

$ git submodule update --init

$ make # "undefined reference to `__android_log_print'"

The reason for the syscalls.cc modification was that, even if I acted like I was just a normal non-Android POSIX box, there was still some residual detection in the build that would mean that Android-specific stuff would attempt to build–and most of these cases existed in that one file.

Luckily, the remaining Android conditional stuff was only complaining about the lack of logging functions to link to, which unlike some other Android libraries, could be linked without issue on-device.

So, I just added it to the LIBS environment variable. (Not LDFLAGS because the Makefile seemed to mess with that a whole bunch before it got to the linking bit)

$ LIBS="-llog" make

$ ./crawl

Luckily enough, this worked! Non-Android DCSS worked in Termux!

Proot

So, I hinted at the beginning of this post that I wanted to get ADOM running natively on my phone. But how could I go about doing that? It’s a closed-source game, so the usual tricks wouldn’t work here.

Well, during my travels, I read about being able to run the Raspberry Pi version of ADOM on Android. This was because the Raspberry Pi version was a 32-bit statically linked ARM ELF, which turns out, was able to run without modification on ARM Android devices!

The keyword here is “was”.

32-bit statically linked ARM ELF binaries can still run on my aarch64 (64-bit ARM) Android phone, but we have an old friend to contend with first: seccomp.

$ wget https://www.adom.de/home/download/current/adom_linux_arm_3.3.3.tar.gz

$ tar xvaf adom_linux_arm_3.3.3.tar.gz

$ cd adom

$ ./adom

Bad system call

stracing the game like we did with Sil reveals that the syscall that’s killing the game for us is setuid32, however, this time we couldn’t just change the source to get around it. So, what’s an Android-based ADOM-player to do?

$ strace ./adom

setuid32(10202) = 10202

--- SIGSYS {si_signo=SIGSYS, si_code=SYS_SECCOMP, si_call_addr=0x1caf70, si_syscall=__NR_setuid32, si_arch=AUDIT_ARCH_ARM} ---

+++ killed by SIGSYS +++

Bad system call

Usually, if I wanted to change a call in a binary I couldn’t modify, I would try to LD_PRELOAD a custom library that would intercept the bad call, but alas, this is a statically linked binary, so trying to change something that would be loaded dynamically would have no affect here.

Enter proot and it’s magic.

$ apt install proot

$ proot ./adom

This…actually kinda worked! What the heck??

At the very least, it didn’t instantly get killed by the kernel. However, looking at strace output again, it also seemed that it didn’t know what kind of terminal I was using, or have any environment, which seemed to be messing things up.

So I passed in the environment that I thought it wanted:

$ TERMINFO=/data/data/com.termux/files/usr/share/terminfo TERM=xterm proot ./adom

And boom! Playable ADOM on Android!

ADOM was probably the most tricky to figure out since there's no source code, and the only ARM version is a statically linked binary that immediately uses a syscall that SECCOMP kills the process for

— Arch 💕 (@Archenoth) April 2, 2020

But it turns out you can just proot it and pass along some curses environment?? pic.twitter.com/8ODBwJ0608

However, there was a catch. Savefiles didn’t seem to work, and for some reason, using qemu-arm with proot seemed to fix it, but in a pretty resource-intensive way.

$ apt install qemu-user-arm

$ TERMINFO=/data/data/com.termux/files/usr/share/terminfo TERM=xterm proot -q qemu-arm ./adom

So, while this worked, it was both heavy, and also no longer technically being run “natively”. At that point, I was mostly just messing around with proot options, seeing if I could coerce it into working somehow without qemu, but with little luck.

But…if proot allowed us to get past the initial seccomp hurdle, that meant that we could likely make something that would work too! Since no code is actually magic, that meant we could definitely do better than we had if we can learn proot’s secrets. So, what can we learn from proot? How is it letting things work?

Enter ptrace!

Diving a little into how proot works, I discovered that the way it allows for intercepting such low-level execution is because of a nifty little library called “ptrace”. I’d heard of ptrace before since that’s what debuggers use–and it’s also what strace uses to peek into what a program is doing as it runs.

From my understanding, proot is a version of chroot that is capable of running without root because it intercepts all the privileged calls with ptrace, and instead uses its own implementations. This allows for the program it calls to “think” it’s doing privileged things, when in actuality, it’s just working within a special environment.

Also, with ptrace, you can’t “technically” stop a syscall from happening, but you can change every part of it before it executes–including the syscall number! So that meant if we wanted to stop a system call from happening, we just needed to change the system call number to be a syscall that was allowed by seccomp. And lucky for us, there is, in fact, a syscall that fits the bill perfectly: -1, the “invalid syscall” syscall. This would turn our target syscall into what is essentially a nop.

That’s exactly what we’re looking for!

So, all we had to do to get ADOM working was write a simple program that could ptrace ADOM and intercept our rogue syscall. There was a little snag though: since I was working on aarch64, none of the documentation I could find gave information that worked on it.

Almost all tutorials mentioned using the PTRACE_GETREGS and PTRACE_SETREGS ptrace calls to intercept and modify syscalls, which unfortunately didn’t exist on aarch64 yet. (Including this very helpful tutorial that helped me in a lot of other ways)

When I looked for alternatives in the list of ptrace calls I could use on this architecture, I found the similarly-named “PTRACE_GETREGSET” and “PTRACE_SETREGSET” calls which seemed like answer, but trying to figure out how to use that on aarch64 once again lead me to a lot of platform-specific documentation that didn’t include the one I was on.

Unfortunately, this made sense, because it turns out ptrace syscall modification involved changing the actual registers of the CPU it was running on, so it made sense that it was going to be very platform-specific. I did eventually find a bug report post that vaguely hinted at using iovecs, which was a lead, but also lead me down a pretty lengthy rabbit hole, since:

- I had never used anything like them before.

iovecrequired an understanding of what was being put into them. (Which I very much lacked)

Luckily, I eventually found the commit where the register struct was introduced in aarch64 on Android, which gave me enough insight about how the registers were structured in aarch64 to successfully guess how to implement a ptrace wrapper I could use for ADOM, and this was the result:

It’s not the cleanest code, and it uses a hardcoded full-path for the location of my adom binary (Which I renamed to adom.bin) so I could call it from anywhere. But after compiling it with gcc ./syscall_intercept.c -o adom, I had a light, working ADOM binary I could move anywhere that worked natively on my phone!

That’s right! After a whole slew of research, I managed to get ADOM to run natively on my phone with ptrace! And if you compile the code above after pointing it at your ADOM binary, you can too!

Conclusion

List of some roguelikes I've gotten to run natively on my phone:

— Arch 💕 (@Archenoth) April 2, 2020

- Angband

- Sil

- FrogComposband

- Crawl

- ADOM

I may have a problem

Honestly, I came into this with pretty low expectations. I expected to either not get very far, or to be underwhelmed by the results even if they did work.

So I was pleasantly surprised when it turned out that roguelikes in Termux are not only possible, but also surprisingly playable! And unlike a lot of Android games I’ve enjoyed before, they take up next to no battery, so you can play them when you’re on a long haul somewhere without an internet connection.

It also turns out that the suspend save functionality of most roguelikes lends itself extremely well to being able to quickly start up and play games for a few minutes at a time, even if you have basically no time to do something more involved.

I’ve ended up sinking no insubstantial number of hours playing Angband, ADOM, and more recently, ToME 2 on my phone during the little bits of downtime I’ve had in my day. I don’t need to sit down and think about playing it, it just kinda “happens” now when I have a few moments to spare and I have nothing else to do.

I don’t know how many more roguelikes I’ll put on my phones, but I can say that I’m all set entertainment-wise if I ever get stranded on a desert island somewhere. And, while substantial, the effort I put into this little experiment ended up being much more worth it than I could have ever anticipated it being!

Now, if you’ll excuse me, I have some Chaos Gates to deal with.

The Blog of Words

The Blog of Words